|

Listen to this post:

|

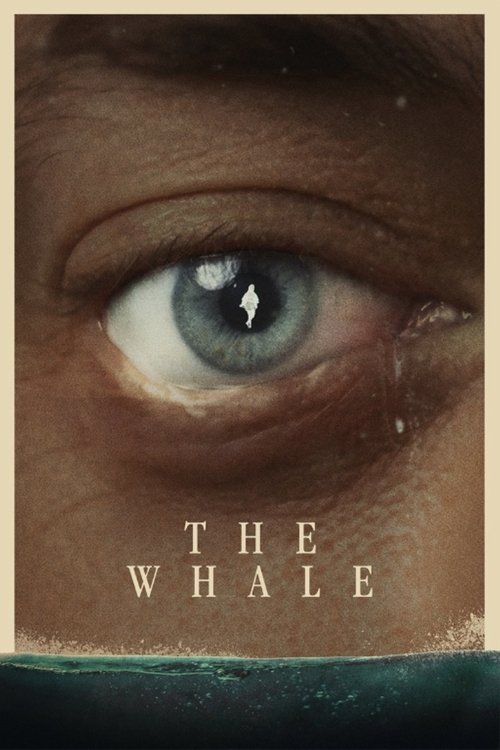

In less than two decades Hollywood went from employing fat bodysuits as objects of ridicule in comedies like The Nutty Professor and Big Mommas House to vessels of emotion in a film like The Whale, the latest from Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream, The Wrestler). We live in a world where a show like My 600-lb Life can be seen as both simultaneously comedic and tragic, our hunger for the world’s oldest entertainment duopoly satiated in a single serving.

So much of this film’s attention has been on Brendan Fraser’s triumphant “return” to a starring role after being unfairly ostracized by Hollywood bigwigs it would be a shame to have his otherwise phenomenal performance be overlooked in what’s really just a so-so film. Unlike its star, The Whale (the film) has trouble carrying the enormous weight of its strained metaphor.

We first see Charlie (Fraser), who is super morbidly obese, masturbating to gay porn on his couch, only to suffer what could be a heart attack while climaxing. Charlie is only saved by happenstance when Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a young missionary from a local end-times Christian ministry, finds him struggling and is able to calm his breathing by reading an excerpt from an essay on Melville’s Moby Dick.

Charlie is so ashamed of his appearance he disconnects his webcam when teaching his online English class, leaving money in the mailbox for his pizza deliveries to avoid human contact with the outside world. The only exception is his friend Liz (Hong Chau), a nurse as much his enabler as she is his caretaker. Shocked by his dangerously high blood pressure readings, she warns Charlie he needs to go to the hospital as he’s likely to die of congestive heart failure in days. When he refuses, Liz realizes that fighting is useless as she hands him yet another bucket of fried chicken.

Sensing this could be the end he phones his estranged daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink) to come over, despite having not seen her in a decade, and agrees to help write her English essays in exchange for handing over his life savings. Angry and violent, Ellie appears outwardly cruel to Charlie, but agrees to write things her way in her notebook. But is Ellie doing it for the money, or does she still harbor feelings for her ailing father?

Based on Samuel D. Hunter’s 2012 play of the same name (Hunter also penned the screenplay), The Whale is very much structured and feels like a stage play, for better or worse. Set in a single location, Charlie’s apartment, characters enter and exit as they’re needed, revelations are revealed, with all the usual strained symbolism you see coming miles away. Worse, apart from Fraser, none of the other performances are especially convincing, the actors pantomiming their roles for the cheap seats as they play second-fiddle to the literal elephant in the room.

If his name didn’t appear in the credits you’d have a hard time guessing this was a film directed by Darren Aronofsky. It’s a head-scratcher that the director of Requiem for a Dream and Black Swan could craft something this…pedestrian. Maybe it’s the limitations of Hunter’s original play that hold back the cinematic potential of this tale of familial obsession. In a way, The Whale serves as a companion to a better Aronofsky’s film, The Wrestler, in showing us the twilight days of deeply flawed men refusing to rise above their own narcissism. Both films even share a pivotal scene where transgressive choices are presented as liberating, though here this moment is much less subtle.

Of course, there’s also the possibility Aronofsky sees the real tragedy of this story and gives us a breadcrumb trail to discover it ourselves. We only see Charlie for what could be his final days, the product of what has obviously been a period of food-induced self-destruction. There are hints the relationship with his deceased boyfriend, a former student, may have been more illicit than stated.

I won’t spoil it here, but there’s no way to interpret the final scenes as anything less than cruel and selfish, Charlie’s insistence his daughter is “perfect” and amazing, despite evidence to the contrary, feels like a reminder that his heightened optimistic outlook could be nothing more than the delusions of a dying man rationalizing his destructive behavior one last time.

There has been criticism of having Fraser don a fatsuit to play Charlie, and even the many health-related issues that most morbidly obese people live with, as ‘fatphobia’ or even exploitative. Aronofsky doesn’t shy away from showing these realities up close. We see the real damage obesity has done to Charlie’s body, the decaying skin, his wheezy breathing. Charlie doesn’t “eat” so much as he force-feeds himself, his expression glazing over while ingesting his high-calorie poison.

The Whale is not a great film, but it has a great performance, easily the best “acting” that Brendan Fraser has ever done. He’s mesmerizing in the role, working flawlessly with the realistic body prosthetics to outwardly convey the inner torment of a man eating himself to death. Fraser is sensational even when the movie is not. I suspect there’s a completely different narrative at work here, a cautionary tale that enabling terrible behavior is perhaps the cruelest action of all. When the nicest person in your movie is the anonymous pizza delivery man, it’s hard to tell who the real hero is.